Hidden in plain sight

The gruelling experience of food delivery workers

Australia's on-demand food delivery industry is bigger than ever, with seven million Australians using food delivery services every three months.

Dominating the estimated 250,000 person strong workforce are international students. They're dependent on gig work to pay their way, yet they lack many basic rights as they aren't considered employees.

These workers are the cogs within the machine of the food delivery, providing a pleasure that's synonymous to the luxuries of modern day society.

This is Rijone. Nine months ago, the 21-year old left his home in Bangladesh to study in Australia.

He's sitting on a bench with his knees up to his chest. It's a mild evening in Melbourne, yet he's rugged up in multiple layers of clothing, prepared for the long night ahead of him.

Since it was his own decision to leave home to study in Australia, Rijone says he doesn’t want to take his family's money.

“So I’m pretty much on my own. That’s why I started doing Uber,” he says.

When asked if he thinks food delivery work is dangerous, he says "definitely".

According to a report published by the McKell Institute, a staggering 66 per cent of full time workers earn less than the minimum wage. Majority of riders are international students, leaving them vulnerable to exploitation. 79 per cent of riders report freelancing across multiple apps for higher income and protection from sudden deactivation.

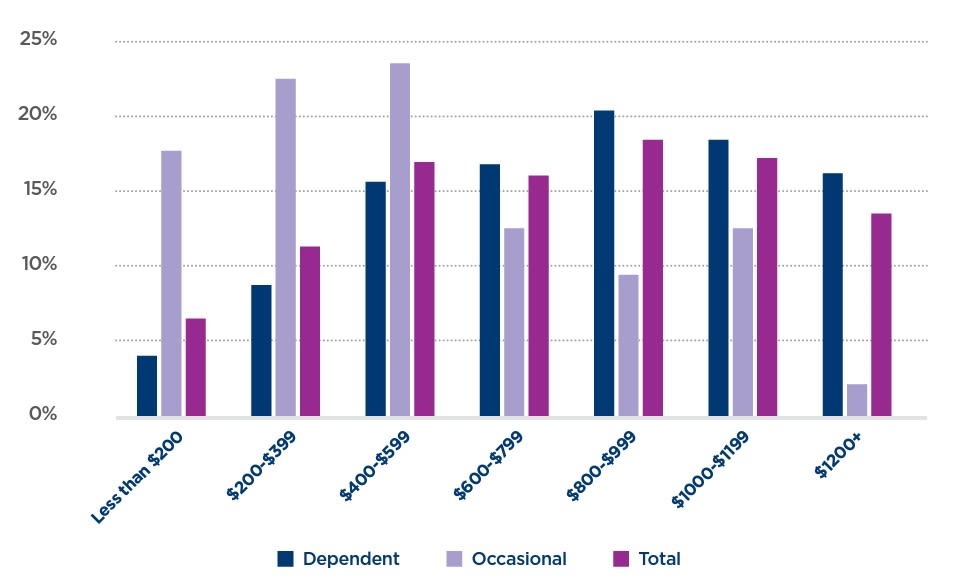

INCOME RANGES BY LEVEL OF DEPENDENCY

The more dependent workers are, the distribution of income flattens out. This shows how hourly rates decrease the longer riders work, leaving full-time workers having to work long shifts, busting the myth that food delivery work is "flexible".

Majority of riders are international students, leaving them vulnerable to exploitation. 79 per cent of riders report freelancing across multiple apps for higher income and protection from sudden deactivation.

95 per cent of workers support regulations to set standards for food delivery.

The recent spate of deaths in the industry has lead to the federal government's new closing loopholes industrial relations bill, set to address many of the issues within on-demand food delivery work.

The bill will secure gig economy workers up to $404 million more pay a year by allowing the fair work commission to set standards for the road transport industry. The gig economy is one of four areas of the reforms, which will provide equal pay for labour hire workers, criminalise purposefully underpaying employees and improve rights for casual workers.

Industrial relations minister Tony Burke said at the National Press Club in August that without minimum pay gig workers are incentivised to ride dangerously.

“Workers run red lights, go up on the footpath [or] down the road… creating an extra lane between parked cars and traffic, knowing at any moment if a car door opens, instead of riding between the lanes, they’ll be lying beneath the traffic.”

Rijone recounts crashing twice in the last three months. On one occasion, the bike slipped and he injured his hand, putting him out of work for two weeks. More recently, he fell off after losing control on a gravel road. He stresses it’s not the riding itself that’s dangerous, but the “pressure to do [the delivery] quick” that causes mistakes.

Rijone's experience outlines the major issues involved with food delivery work. Extremely poor wages demands riders to conduct risky behaviours, even though they're not entitled to sick pay or compensation.

source: supplied

source: supplied

"That's the pressure, you know."

The role of algorithms on food delivery platforms have received scrutiny around the way algorithms police and manage its workers. The algorithms determine which courier receives which job, based on the courier's geolocation, previous performance rating, and other indicators. It's just like key performance indicators within the workplace, but taken to a whole new level.

Academics have investigated the role of algorithms in food delivery work ever since its birth. These articles lay bare how algorithms are impacting workers

Algorithms at Work: The New Contested Terrain of Control

Algorithms direct workers by restricting and recommending, evaluating workers by recording and rating, and disciplining workers by rewarding and replacing.

Politics of on-demand food delivery: Policy design and the power of algorithms

By determining where and when, algorithms push couriers to be creative with how, often at great physical risks, economic costs, and emotional toll.

Riding Against the Algorithm: Algorithmic Management in On-Demand Food Delivery

The unique features of algorithmic management such as persistent surveillance, continuous performance assessment... little human-to-human contact... facilitate important power asymmetries between workers and management .

This is Daisuke.

Visiting Australia on a working holiday visa, the 24-year old from Japan pays his way working for UberEats.

His experience with food delivery work only affirms what we’re currently hearing from the workers. It also lays bare one fundamental right that food delivery workers are stripped of - a dedicated toilet.

“Ah, it’s a big problem,” Daisuke says with a laugh. It’s obvious that this is a challenge he navigates every shift.

Food delivery workers have to utilise toilets inside of shopping centres, public toilets, or even at times hassle restaurant owners if they can use their bathroom.

“There’s some McDonalds and Hungry Jacks,” he says.

“Sometimes [I ask] the restaurant worker, ‘Sorry, do you have a toilet?’”

However, fast food restaurants often close their toilets later into the night, leaving food delivery workers with nowhere to go.

When he has to, Daisuke says he "uses the park" to relieve himself.

Rijone says he utilises shopping centre’s bathrooms as well, but if no toilets are open, he tries to “hold it in”, because otherwise, he’d have to go back home.

“Then that way, I'm just wasting my time," Rijone says.

This issues is what Andrew Copolov’s Gig Worker’s Hub seeks to address for food delivery workers. The hub is a space where food delivery workers can rest, go to the toilet and chat with other workers. It’s a sanctuary from the chaotic streets of Melbourne.

An architecture PhD student at Monash University, Copolov worked as an UberEats rider himself to deepen his understanding of the industry. His experience as a rider was "a confirmation of what I had been hearing from other riders", he says.

While issues such as poor pay and workers' entitlements can be solved are being addressed by Labor's closing loopholes bill, it won't be able to address other problems, such as social isolation.

"And that's where we need other things, like for example, dedicated spaces and amenities for these workers."

Since international students make up a large majority of food delivery riders, they haven't had time to accustom themselves to Australia's roads, suburbs and culture. RMIT associate professor in the School of Media and Communications, Catherine Gomes, says better and more accessible education for food delivery workers is crucial.

"What happens is that they have very little idea about road rules. Many of them come from countries where you do not share the road with trams.

“Even though all these companies provide their delivery workers with… some sort of training, it doesn’t mean that half-day training is absorbed,” she says.

That’s what Swinburne University’s International student driver safety program aims to do. Developed in collaboration with Study Melbourne, the program’s website states it will help international students to “better understand what it’s like to be a food delivery worker in Victoria.”

Labor’s closing loopholes bill has garnered a lot of support, but it’s also received a fair amount of criticism from employer groups and the opposition.

The Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry chief executive, Andrew McKellar, said “the only winners in this are union chiefs”. The opposition leader, Peter Dutton, also rejected the bill, accusing Labor of pursuing a union agenda.

However, the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) disagreed with exemptions for businesses with 15 or fewer employees, calling for rules which apply to all businesses equally.

The bill has received in principle support from UberEats yet it claims food delivery prices could surge by 85 per cent, which lead to the business lodging a submission for a senate inquiry into the legislation.

Industrial relations expert at the Australia Institute, Fiona Macdonald says Uber’s warning reveals food delivery workers are already poorly paid.

Speaking to The Guardian, she says “What that is reflecting is the current below-acceptable levels of pay being received by the current workers.”

Despite these criticisms, the stance of food delivery workers is unanimous. With 95 per cent of workers supporting industry regulation, it’s hard to argue against it.

Copolov says these workers are at the "heart" of the production of money today. "Money isn't just coming from producing things. It's coming from distributing things."

What's evident is that these workers suffer greatly to provide the luxuries that're many take for granted.

"They're being made effectively invisible by the work they're doing."